When he was 12 years old and still living in Jamaica, Wes Hall remembers his mother beating him so badly in public that a passing one-legged man tried to intervene.

“He said to my mom, ‘You should stop beating that boy. One day that boy could be the one that you rely on to look after you,'” Hall is now a leading Canadian businessman.

Hall went on to become a leader in Canada’s corporate landscape, as founder and executive chairman of Kingsdale Advisors and one of the stars of Dragon’s Den on CBC. In recent years he has also become a prominent anti-racism advocate.

Hall tells the story of the sacrifices that made him a success in his new memoir, released earlier this month, called No Bootstraps When You’re Barefoot: My Rise from a Jamaican Plantation Shack to the Boardrooms of Bay Street.

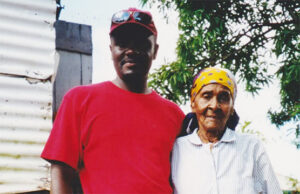

He and his two siblings were abandoned by their mother as very young children. Along with some of their cousins, they were raised by his grandmother, Julia Vassel, in a tin-roof shack without electricity or running water in St. Thomas, Jamaica.

Vassel would rise at 4 a.m. daily to prepare food for Hall, his siblings and their cousins, before heading to work on nearby plantations at 6:30 a.m. At one point she was supporting 10 children on her plantation worker’s salary.

In 1985, a 16-year-old Hall moved to Canada to join his father in Toronto. He got his high school education, and then found a mailroom job at a law firm downtown on Bay St.

Entering the heart of the city’s financial district showed Hall the kind of life that he wanted to lead, but he didn’t realize at the time that “there were no Black people in those corner offices, or in any of the offices for that matter.”

Having grown up in Jamaica, Hall was used to Black people being in positions of power in all walks of life, from school principals to local business leaders to police officers and judges.

“To me, being Black was never an obstacle to being successful. Being poor was an obstacle, but being Black wasn’t,” he said.

It was only years later — as he was already enjoying success in a vice president role on Bay St. — that he overheard a conversation between the two most senior people in the company’s Toronto and New York finance departments.

“The guy in the U.S. said, you know, to the Canadian guy, ‘In spite of the fact that Wes is Black, he’s doing well,'” Hall remembers.

Looking back, Hall began to realize racism had played a role in earlier parts of his career. But he now says that while these realizations were difficult, they didn’t have a lasting impact on his psyche.

“It certainly didn’t hurt as much as when I was hearing it from my mother. So she’s certainly hardened me for the life that I would live here in Canada,” he said.

As his success grew over the years, he’s worked to try to make sure other Black, Indigenous, and people of colour don’t have to face the same challenges he did.

In 2020 Hall founded the BlackNorth Initiative, asking Canadian business to tackle systemic racism in their organizations. The move followed global protests over the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin.

More than 200 Canadian organizations signed on, but a recent investigation found that only a minority had made significant strides in hiring more Black employees, or elevating them to executive levels.

Hall said about 40 per cent of signatories to the initiative are committed to its ideals, and have plans in place to achieve them.

A further 30 per cent want to do something, but don’t know where to start, which is why his organization has created a “playbook” to give them direction.

The remaining 30 per cent might have signed on performatively, to allay public scrutiny, he said.

The work of BlackNorth is helping those companies to make the cultural changes needed for BIPOC employees to thrive, which will take time “to filter into the culture of the business because it didn’t exist before,” he said.

“It’s to change my kids’ lives, so that when they graduate from university and they get into the workforce, they don’t have the struggles that I had.”