By Lincoln DePradine

In more than 70 years in Canada, Bromley Armstrong faced death threats, experienced racial discrimination firsthand and suffered health problems in an endless struggle for equity and human rights for all people. But Armstrong – who died last Friday at 92 – never has had any regrets about his actions and was unapologetic to his last day.

“If I had to do it all over again, I would do the same damn thing. I feel I made a contribution and that’s very important to me,” he once said.

Armstrong, a former commissioner on the Ontario Human Rights Commission, earned several deserving titles including community organizer, mentor, guidance counsellor, mentor, author, newspaper publisher, human rights advocate, and outstanding trade unionist.

“He was a champion for human rights. He was very committed to the struggle for human rights,’’ said retired trade unionist June Veecock.

For two decades, Veecock was director of human rights for the Ontario Federation of Labour. She was the first recipient of the Toronto & York Region Labour Council’s “Bromley Armstrong Human Rights Award’’.

“I’m proud of that award,’’ Veecock told The Caribbean Camera. “I worked with Bromley Armstrong on several projects and learnt a lot from him. I valued his support and he was always willing to give advice and point me in the right direction.’’

Armstrong, the fourth of seven children, was born February 9, 1926, in Kingston, Jamaica.

He and his brother, George, arrived in Toronto on December 11, 1947. He often related engaging and entertaining stories about his early winter experience and on general conditions in Canada on his arrival here.

“When I arrived, there were 1,600 black people in Toronto,’’ Armstrong recalled in an interview a few years ago. “We had one black lawyer, no doctor, no dentist. Not even a garbage collector.’’

Like many Black immigrants – then and now – Armstrong had trouble obtaining employment in Canada, finally landing his first job with an agricultural equipment manufacturer.

It was in that job that Armstrong began his involvement in union activism, became a spokesperson for the disadvantaged – including Jews and whites displaced from eastern Europe – and proceeded into broader community issues dealing with racial equality, human rights reform and social justice.

Armstrong’s dogged efforts helped to regularize the status of many Jamaican workers who were brought to Canada in the early 1900s as domestic workers by wealthy Canadians.

He also was in the forefront of public campaigns against discrimination including “sit-ins” at restaurants in Dresden, Ontario, where restaurant service was being denied to African-Canadians. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Armstrong and another person, Ruth Lor Malloy, exposed a systemic policy in which landlords in Toronto refused renting to Black people and other minorities. Eventually, a series of anti-discrimination laws was passed in Canada.

Armstrong was the youngest member of a 1954 delegation that went to Ottawa to protest the federal government’s restrictive immigration policy that “closed the door” to people of African descent and other visible minorities. The delegation was led by the late Barbados-born Donald Moore, who died in 1994.

“The Canadian government, at that time, despite the post-war boom and the growth in manufacturing, did not want Black people in this country,” Armstrong had said. “A White Jamaican could get into Canada with no problem. But a Black Jamaican could not.’’

Jamaica-born trade unionist, Kingsley Gilliam, migrated to Canada in 1969 and remembers travelling from Sudbury to Toronto to participate in conferences and other community activities. “Bromley was one of the leaders in the community at the time,’’ Gilliam said in an interview with The Caribbean Camera.

Gilliam, who himself became a human rights advocate and now is an executive member of the Black Action Defense Committee, said Armstrong “groomed’’ and “mentored’’ him.

“I consulted him on numerous issues I was undertaking in the community,’’ said Gilliam. “We consulted regularly and we had extensive communication.’’

Armstrong, who once served as an adjudicator with the Ontario Labour Relations Board, led the formation of the Caribbean Soccer Club in 1949 and was the first black insurance agent in Canada. He would later quit the Cooperators Insurance to set up his own insurance business.

From 1973 to 1997, Armstrong published The Islander newspaper. Jules Elder, then enrolled at Centennial College, was involved in the paper as a journalism student.

“I was awarded a scholarship by the Trinidad and Tobago government and was aware of Bromley Armstrong’s involvement dealing with issues of racism in the Black and Caribbean community in Canada,’’ said Elder, now a veteran editor and media educator.

At The Islander, he said, “I was given the opportunity to volunteer and develop as a journalist’’.

As a student and young journalist, added Elder, “Mr. Armstrong was someone I could always turn to for guidance. He found the time to meet with young people and to listen to their concerns’’.

Police arrested 29 white supremacists after repeated threats against Armstrong and his newspaper.

Armstrong, the father of five, was a founding-member of several organizations including the Urban Alliance on Race Relations, Black Business and Professional Association (BBPA), Jamaican Canadian Association, National Council of Jamaican and Supportive Organizations in Canada, and the Canadian Ethnocultural Council.

He also served on the Toronto Mayor’s Committee on Community and Race Relations, Ontario Advisory Council on Multiculturalism, and the board of governors for the Canadian Centre for Police Race Relations.

In recognition of Armstrong’s lifelong human rights and social justice achievements, he received numerous awards including the Order of Distinction in Jamaica, the Order of Canada and the Order of Ontario.

As well, he received an honorary doctor of laws degree from York University and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the BBPA.

Armstrong retired from working in 1996, spending more time with his wife, Marlene, at their home in the City of Pickering.

In describing his 1972 marriage to Marlene, a fellow Jamaican, Armstrong called it “the best part of my life’’. The marriage, he said, “rejuvenated’’ his life.

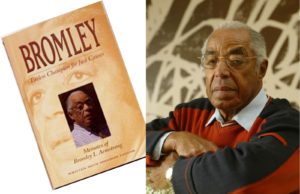

Armstrong has documented his life experiences in an autobiography titled, “Bromley: Tireless Fighter for Just Causes’’. The 256-page paperback was published in 2000.