When 18-year-old Jayden Dill was picking his courses for his last year of high school, something wasn’t sitting right with him.

Looking back at a dozen years of school in Mississauga, Ontario, he felt like he didn’t see much of himself and other Black people represented in the books he had read and the topics he had learned.

Mostly, he realized that he had never learned about the full history of Black people in Canada.

He wanted to make sure that wasn’t the case for future students.

Two years later — after much campaigning and hard work — he and two other Black students at his school found out that their fight to get a Black history course added to their high school curriculum had paid off.

A new course called “A History of Black People in Canada” will launch at Our Lady of Mount Carmel Secondary School in Mississauga in September.

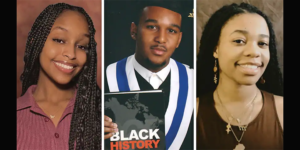

Jayden, along with Hireé Dugassa, 17, and Kiya Busby, 17, say they want to see their fight happen in schools across Ontario.

It’s difficult to summarize what Black history education looks like across Canada since each province and board has its own curriculum guidelines.

In Ontario, teachers are given certain expectations of what they should include in their classes, but they ultimately have the power to choose which textbooks to use and what to teach as part of a history course.

Michelle Coutinho, the principal of equity and inclusive education at the Dufferin-Peel Catholic District School Board, said part of the problem is that teachers are using resources that are narrow in scope.

This may limit a Black history course to specific milestones, like the emancipation of slavery or figures like Martin Luther King Jr., or the story of Viola Desmond, a Canadian woman who now appears on the Canadian $10 bill.

She said teachers might not have the awareness to teach beyond these events because that’s what was originally taught to them.

“Perhaps it’s an instinct, that teachers have learned over time in their own experience that these events might be what’s taught,” said Coutinho.

Like Jayden, she says Canadian history needs to be broader.

“That involves the long-standing history of the Black community and the long-standing history of Indigenous people,” said Coutinho.

“All of that has to be represented in a full history program.”

Coutinho says that the board is actively working to help their teachers be more aware of these issues around the resources they’re choosing.

Jayden started his fight for more Black history back in February 2020, shortly after choosing his courses for his graduating year.

He used Snapchat to survey students in his school about how they felt about the lack of Black history in the curriculum.

Not long after, George Floyd was killed by a police officer in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, and Black Lives Matter protests broke out across the globe.

That’s when Jayden, who is now in his first year studying journalism and political science at Ottawa’s Carleton University, says he knew he had to address the concerns he and his peers were having.

After the summer of racial reckoning, Jayden returned for his Grade 12 year and began his work on what he called “the Black history course project.”

When he pitched the idea to the administration, he was told that course creation can take years and that it might be an ambitious goal.

Jayden began emailing Canadian politicians, principals and school counsellors about the project, detailing the interest he had seen among his peers for a Black history course.

After not hearing anything back, he knew he needed to create more momentum.

In January 2021, Jayden approached two other Black students, Hireé and Kiya, to see if they could help amplify his call for a Black history course to be taught in their high school.

Hireé and Kiya, who were in Grade 11, had just started a project of their own called “the Black Voices Lab.”

This involved weekly meetings with educators to discuss the needs and concerns of Black students.

They began drawing attention to Jayden’s project, and asked students and community members to sign a petition calling for a Black history course in their school.

Meanwhile, to strengthen their case, Jayden began working with a teacher to inform what course materials would be recommended.

Using three different textbooks, they began patching together a history of Black people in Canada.

This went beyond merely the end of slavery, which Jayden says is one of the only things he learned about Black people in his history courses at school.

For example, Jayden included the history of the many Black people who immigrated to Canada in the mid-20th century.

Jayden actually had a personal tie to that part of history, as his parents were two of many who immigrated from the Caribbean.

After gathering hundreds of signatures from students and community members and presenting a full plan for the course, Jayden, Hireé and Kiya waited to see what would happen.

Administrators agreed to start offering the course at the school and made a plan to launch it in September 2021.

Due to some hiccups, that initial timeline didn’t pan out, but this past January, Jayden, Hireé and Kiya found out that their hard work had paid off. They received word from school administrators that the course they fought for would begin running for the first time in September 2022.

Kiya said she was thrilled to hear that the course was being offered, since the version of Black history she was taught in high school was lacking.

“Black people [in school teachings] are reduced to nothing more than slaves basically, with the exception of major historical figures like Marthin Luther King Jr. and Harriet Tubman,” said Kiya.

Hireé agreed that having a simplified version of Black history can be harmful.

She said its still important to acknowledge the harm and racist actions that have been inflicted on Black people, including slavery, but that celebrating Black culture and accomplishments is also important in painting a fuller picture.

Jayden said that teaching Canadian kids about Black history is important for so many reasons, but most importantly, it’s about telling the truth.