By Cecil Foster

There is an old saying that the big difference between writers and those who think they can write is that the writers actually write. I think of this adage when I reflect on the life and death of my now departed friend and mentor Austin “Tom” Clarke.

In our conversations, he always called me Foster or Fos—rarely Cecil—in the British high school tradition to which he and I were exposed in Barbados. I called him Clarkie, also in keeping with that tradition. Perhaps there is something in that “Little England” way of showing respect by addressing each other by surnames, but yet also so Caribbean and even black in the way we improvise. Naming is respectful, a story in itself. And that is one of the big things I learn from Clarkie.

Rarely would our conversations end without Clarkie asking, “So Fos what you working on? What you writing now?” And indeed, one of his complaints was that I was not devoting enough time to writing, especially fiction. Once when struggling with a manuscript I told him by phone from Halifax that I was going to give up writing fiction. His response was quick. “No man, you can’t do that. You have too much talent not to be writing fiction. I just wish you would be writing more and reclaim your place as a top black writer.”

And we would talk about the craft of writing— for example, whether it is necessary as black and Caribbean writers to use patois or broken English or whether we should aim to capture the cadence of our languages. That is the pattern that he and I followed, our way of acknowledging that our intended audience is wider than the communities in which we lived.

For Clarkie, writing was a job, a craft that was demanding and required application 24/7. One night, perhaps it was in the 1980s, a group of us were drinking at a bar at the Four Seasons Hotel then located at Yorkville and Avenue Rd in Toronto. Those were the days when LED watches that alarmed were popular. Just before the last call I heard this noise and saw Clarke resetting his watch. “My alarm,” he explained. “I set it for 2 AM for me to be writing every night.” And he wrote every night, and day too, often listening to jazz in the background. For a time he would listen to CBC Radio 2 because of the jazz.

I remember a conversation with Clarkie when he knew he was nearing his end and as he persevered to ensure the publication of his last book Membering, in a way that would be faithful to what he wanted as a final memoir. He was resisting some suggestions for changes to the text or that he should even give up writing and retire. Clarkie recalled how he was inspired by the famous Canadian author Morley Callaghan. “Morley told me, never stop writing, that they will have to carry him out by dragging him away from the typewriter. And that is how I feel too. They will have to drag me away.”

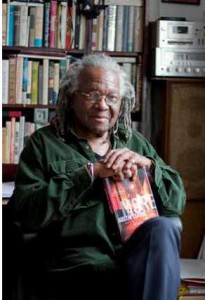

The result of this mindset is an incredible oeuvre on the human condition, primarily as it applies to poor marginalized people, especially from the Caribbean and living in Canada. Most of it is in fiction but later in life Clarkie returned with acclaim to an earlier love—poetry. And in this body of work Clarkie lifted up all of us who aspire to be writers, who know we have stories to tell, and who believe that despite great odds our stories will/must be published, for our stories are important too. This is why he was the pioneer promoting Canadian literature as multicultural, and why he encouraged just about everybody to write.

I shall miss just talking with Austin Arindel Chesterfield “Tom” Clarke. Rest in peace.

Cecil Foster spends his time between Toronto and Buffalo, where he is the chair of the Department of Transnational Studies, SUNY, University at Buffalo.