By Lincoln DePradine

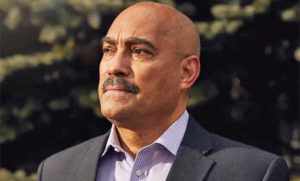

Trinidad and Tobago and Uganda are two examples of developing nations battling the Coronavirus pandemic and that are in need of vaccine support, says Dr Akwatu Khenti, chair of Toronto’s Black Scientists’ Task Force on Vaccine Equity.

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, saying he was tired of receiving calls about COVID deaths, last weekend reimposed a 42-day lockdown in the East African country.

Trinidadians are also under severe restrictive measures, with a COVID case count close to 31,000 and Coronavirus-related deaths at more than 740.

“Uganda is in a mess. They lost eight doctors last week to COVID, and Trinidad and Tobago has the Brazilian variant,’’ said Khenti, commenting on the report of his task force that held 20 virtual townhall meetings, from February 1 to June 9, “to provide the most up-to-date evidence-based advice on the various facets of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as vaccines, especially addressing myths and misinformation’’.

Manufacturers, beginning last December, released COVID vaccines such as one produced by Johnson & Johnson, as well as others such as the Pfizer, Moderna and AstraZeneca.

It is reported that about one percent of people in the Caribbean and Africa is vaccinated against COVID-19; while, 75 percent of all vaccines has gone to 10 countries worldwide. “This is a scandalous situation,’’ said Trinidad-born Khenti, whose task force submitted its final report last week to the Toronto Board of Health.

The report includes data on the negative impact of COVID-19 on African-Canadians, revealing that “members of Canada’s Black communities are more likely to be hospitalized with severe COVID-19 symptoms and to succumb to the disease than their fellow Canadians’’.

It calls for “committed doses of vaccines to immunize Black people delineated as being at disproportionate risk for severe COVID-19 illness, hospitalization, and death’’; appeals for the continued “collecting and reporting regularly on race-based data related to COVID-19, vaccination uptake, and other health matters’’.

Another of the report’s demands is for the City of Toronto to “support priority door-to-door vaccine distribution to individuals in communities with significant technological, transportation and mobility barriers’’; to back “walk-in vaccinations with simplified registration requirement’’; to ensure that vaccines are “set aside specifically for members of high-risk Black and racialized communities”; to put in place safeguards to “sustain mental wellness checks and case management services through trusted community partners for at least two years after the pandemic’’; and that “culturally sensitive online and telephone services should also be maintained for a post-pandemic two-year period’’.

The Black Scientists’ Task Force on Vaccine Equity also calls on the city to develop a “mental health strategy for its Black communities,’’ proposing a “parallel rollout of public health education and resources across the City of Toronto to educate Black residents about intersecting mental health and racial stigma risks, especially potential mental health problems among children and youth. These efforts are needed to reduce increasing disparities of mood and anxiety problems and provide a stimulus for Black people to protect their health, with priority accorded to children and youth.’’

The task force also is calling on Toronto politicians to support a World Health Organization (WHO) initiative aimed at saving lives from the COVID virus in developing countries, such as Uganda and Trinidad and Tobago.

“We asked the Canadian government to contribute 75 percent of their surplus vaccines to the WHO,’’ Khenti, a university professor and specialist in health and policy equity, told The Caribbean Camera.

“We also asked them directly to give 25 percent of their surplus vaccines to Black countries, where we are from. We have relatives who are facing COVID without a vaccine.’’

“The current global access to COVID-19 vaccines support the premise that Black lives do not matter globally. High-income countries have secured an over-supply of available vaccines whilst many countries have no access to COVID-19 immunization. Low-risk persons in high-income countries are thus afforded more life-saving prevention than high-risk persons in low-income countries,’’ it said.

“Improving global responses to the needs of Black populations improves local confidence in government by Black populations. This worldwide pandemic will not be resolved until global vaccine needs are adequately met and the virus is effectively contained.’’